Blue Lotus Blues

Lojithan Ram’s Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum

A dried-up pond is oft abandoned by waterfowl

Much like the unfaithful during troubled times

However, the waterlilies and the lotus linger,

Deeply rooted like the unyielding who weather every season.

– Avvaiyar, Moothurai 17

The summer of 2024 was my first summer in America and my last season in Washington, DC. I spent my time working through a bucket list; I was insistent on ticking every box, sometimes even impractically. Like when I made Austin and Noah go with me to the Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens on a day designed to melt even time. In the summers, DC turns tropical, it is hot, wet, and mosquitoes shadow you everywhere. Most people hate it, but for me and AK, it reminds us of Colombo and Bihar. So you can understand, I had to see the lotus and water lilies, in full bloom.

At Kenilworth, the ponds were alive with light. Waterlilies with tight, sculpted petals floated low, their waxy leaves forming an accidental choreography. The lotuses stood taller, bold and open, swaying in conversation with the sky. They did not float—they rose. Above the water, above the muck, above even the reeds. Some were pale pink, others nearly white. One bloomed from the thinnest crack in the mud, its stem stretched like breath held too long. I watched it and thought of home.

In Sri Lanka, the lotus flower is a symbol of nation and state, for some it represents belonging. Seeing a lotus anywhere is a sign of familiarity, like the motel in Plano with the word “bathroom” written on the door in every language, including Sinhala. Seeing vasikiliya in Texas is a humorous hug.

But symbols shift. After the SLPP adopted the lotus as its political emblem, and then steered the country into an economic collapse, the flower was a disgraced symbol. During the aragalaya, placards distorted the lotus, breaking its symmetry, accusing it of betrayal. What does it mean when your national flower, your emblem of dignity, is hijacked by power? What happens to memory when the symbol you clung to becomes the very thing you must resist?

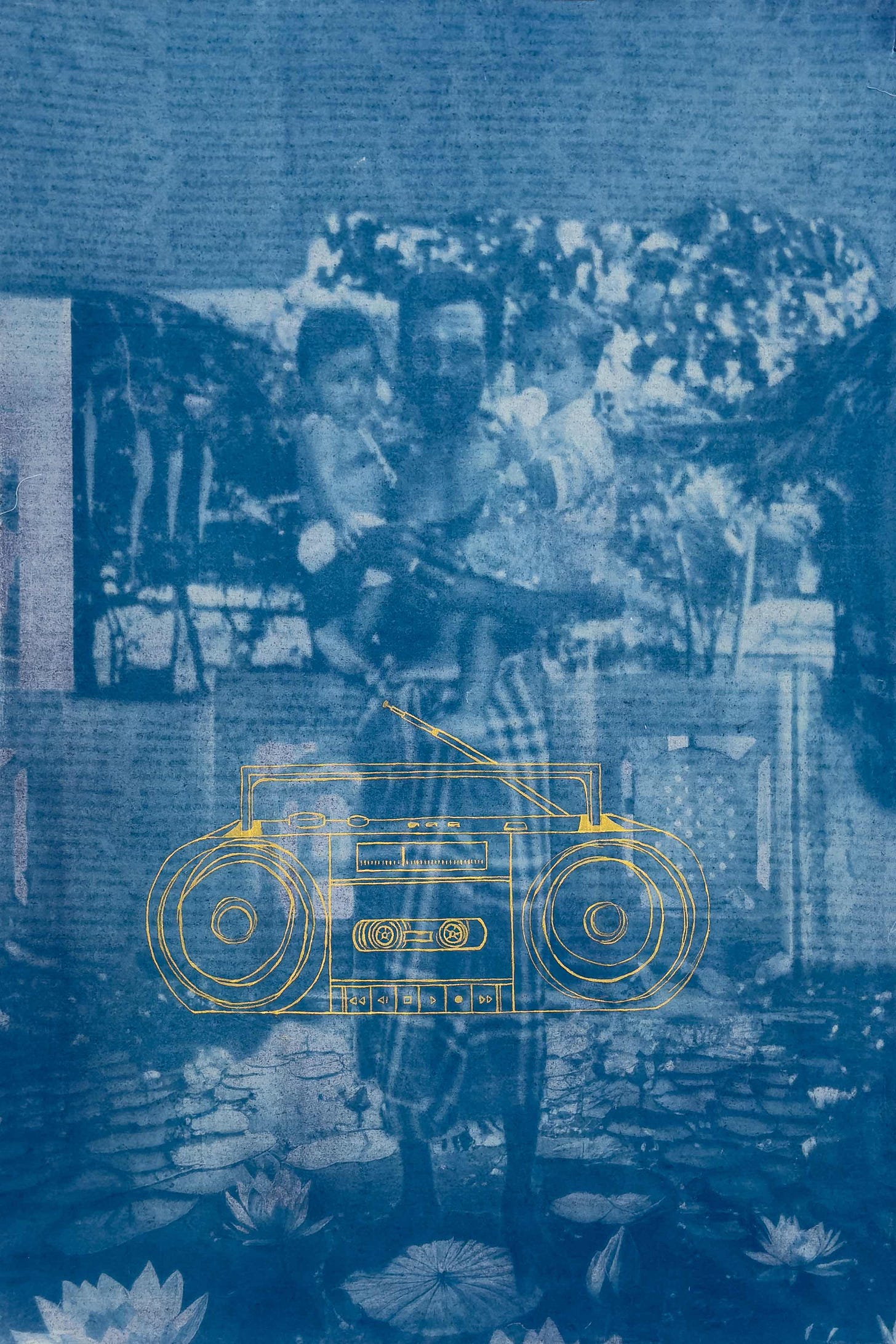

Lojithan has a blue lotus sewn on his pants, and he says, “I am currently at my 24th home, but in my first one, Aloparibilas in Kurumanveli, Batticaloa, there are lotuses everywhere.” The lotus travels with him, from Batticaloa to Jaffna to Colombo. Through this exhibit, he invites us into a tapestry of homes, like a quilt stitching each square with the color blue.

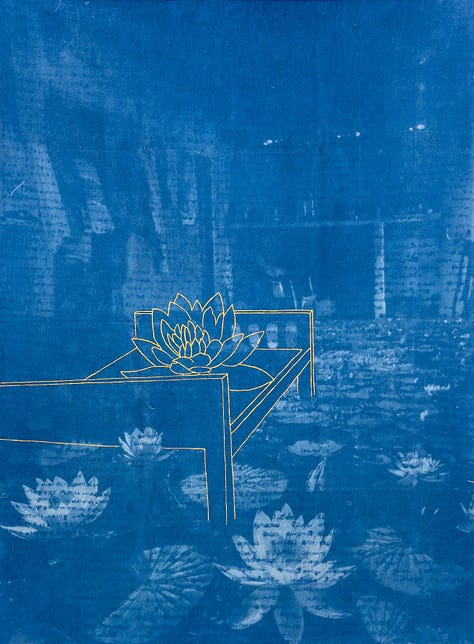

He is a cartographer of his family archive–Lojithan’s first home, which he and his family often return to clean, appears repeatedly, particularly the bed which sometimes takes the form of a lotus and other times is crowned with a lotus.

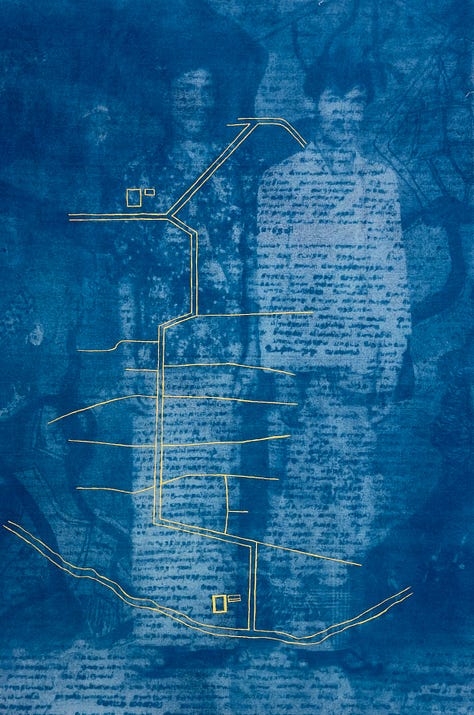

In another piece, he weaves a map of his uncle's two homes, one of childhood and one of marriage, neither of which were safe when he “got disappeared.” Lojithan echoes this idea of not being able to survive where one belongs. The paddy field in front of his uncle’s new home is where he hid assuming it was safe–it used to be, it is where they would fly kites in the off-season.

In addition to a map of homes, Lojithan has rooted his archive in an ancient chant, family photo albums, and the brown paper bags. Through these elemental structures, he composes a quiet symphony of ritual.

He takes us to a towering vertical cyanotype—hung like a banner—that features a faint, almost spectral image of Lojithan’s father, riding his bicycle stacked with brown paper bags, made from repurposed cement sacks. The image spills to the floor, where it meets a sculptural pond of lotus blooms and lily pads, arranged meticulously on a matching cyan ground.

The composition feels sacred and intimate—as if memory itself is being offered at an altar. His father, a figure of quiet ingenuity and care, is elevated to devotional iconography, not through gold leaf or marble, but through cyan light and everyday labor. He is in motion, about to pedal forward, carrying the weight of a humble profession with grace. It bridges memory and motion, devotion and domesticity. Lojithan doesn’t simply depict his father—he enshrines him. The bicycle becomes a mobile altar, a vehicle of care, and the lotus pond beneath it is both rooted archive and spiritual terrain.

And then there is the radio and the funeral chant—Vaikuntha Ammanai. “My uncle chanted it once and asked me to record him. I didn’t know why at the time.” Later, Lojithan would discover that the Tamil-speaking Hindu people in Batticaloa are the only community to practice this chant in Sri Lanka. Even though the chant originated in Tamil Nadu, a single publishing house in Chennai, and a very few personal archives in India are still preserving the ancient palm-leaf manuscripts discovered from the temple and the printed publication in different eras. “Apparently it must be rewritten every 300 years and given to a temple or a king.” When his uncle passed, there was no one left who could read or recite it. The text—once held in hand—could not be understood, so they played the recording of his voice at his own funeral, for thirty-one days. The chant becomes a metaphor for the exhibition itself: archival, yet alive.

Explaining cyanotypes Lojithan recalls, “and blue…I guess we use blue for sadness, for sad things” but there was hesitation, a knowledge that to simplify his journey to grief is incomplete. Perhaps, the blue is actually the blues.

As James Baldwin once wrote, “The blues is a tale of sorrow told in such a way that the teller can continue to live.” Lojithan’s art carries this same ethos. His cyanotypes return to the same gestures—a bed, a chant, a thirusti pumpkin, a field—not to explain them, but to hold them in rhythm. The repetition is not fixation; it is reclamation. The blues does not resolve grief, it repeats it and gives it form without finality. In Baldwin’s terms, it is a refusal to lie about suffering, and a refusal to be broken by it.

If the lotus is what remembers, the blues is how we survive the remembering.

The word blueprint comes from the early photographic process known as cyanotype—kyanos (Greek for dark blue) and typos (meaning mark, impression, or figure). It was a way to fix light into memory, to record architectural plans in reverse: white lines on a field of blue. Although Lojithan’s work does offer some literal cartography, through his alchemy, the cyanotype becomes a blue print—an impression of absence, a grief structure, an archive of what endures in fragments. They are not blueprints for construction, but for remembrance. What emerges is a kind of architecture made of shadow, thread, breath, and bloom. In this way, his work recalls Baldwin’s understanding of the blues: not as lament, but as a structure for survival. A way of saying: this was here. Or maybe even: this still is.

Lojithan’s images do not seek catharsis, they offer continuity. Lojithan’s work, like blues music, returns to its own refrains: the house, the field, the bag, the chant, the father. Not to resolve them. But to honor what survives; his work is not elegy—it is testimony. It insists that what is untranslatable can still be traced and stitched.

Before it can bloom, the lotus seed must be nicked, broken open; it teaches us that germination requires wounding. Even when the pond dries, the tuber sleeps in the mud, waiting. Waiting for the return of water, for the right light, for the memory of rain. This cycle—mud, bloom, decay, return—is not only botanical, it is ancestral ritual.

I was able to enjoy the lotuses last summer because Walter B. Shaw, an amateur gardener, imported a few lotus tubers from Japan or India in the 1880s. Foreign to Washington, D.C., yet perfectly suited to its hot, marshy summers, the lotuses took root and flourished. They transformed swampland into a sanctuary. They lingered and hundred years later, I got to visit them and feel at home from 9000 miles away.

Lojithan Ram’s exhibition, Arra Kuḷamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum, wrestles with this same possibility—of what it means to plant the sacred in unfamiliar soil, to carry something delicate and resilient through time. In his work, the lotus is neither pure nor ornamental. It is an embodied archive, a mapping tool for his family’s history. His village in Batticaloa is drawn not with borders, but with cyanotypes, stitched fragments, devotional chants, and lotuses. Not the glossy lotus of statehood, but the one that blooms in neglected kulams, the one that knows the names of grandmothers, the one that remembers funerals, disappearances, lullabies, and chants that no one can read anymore.

In Buddhism, the lotus flower is interpreted as a symbol of detachment because the large, round leaves are hydrophobic, meaning water beads and rolls off. As Lojithan walked and talked us through his exhibition he referred to his trauma of moving with so much ease and enlightened acceptance. It is as if through all his work in honoring the lotus, he now embodies this botanical marvel. In painting and making the blues, he has become it, transmuting pain into beauty.

What makes Ram’s work resonate is its refusal to romanticize or politicize return. He does not claim victimhood or exile, he does not wear the lotus as a badge on his heart or a chip on his shoulder; he speaks instead of non-belongingness, wearing the lotus on his leg, a shadow he has befriended.

Swamps are often dismissed as dirty, mucky, or uninhabitable. But it is precisely their saturation, their resistance to neat containment, that makes them vital. Ecologically, wetlands filter water, absorb floodwaters, store carbon, and offer refuge to countless species. Emotionally, they mirror what we cannot polish or pave over. They are refusal embodied—spaces of rot and rebirth, of stillness and overflow. People want to drain them, contain them, make them productive. But swamps don’t care to be tamed.

If the swamp is the geography of grief, then funk is its rhythm. Funky things ferment. They resist sanitization. They smell, they swell, they move sideways. In Gypsy & The Bully Door, Nina Angela Mercer’s “funk conductor” leads us not out of the chaos but through it, with GoGo percussion, a descendant of the blues, as ritual compass. In Ryan Coogler’s Sinners, too, the swamp becomes a stage where redemption and pain spiral, where Black blues and wetland spirit worlds entwine. These works share a sonic and spiritual kinship with Lojithan Ram’s cyanotypes: each piece is funky, warped by water, rooted in feeling. They are not tidy, overlayed with photography, painting, handwritten text. They are what Baldwin might call something wild and potent enough to survive. Ram’s work is not nostalgic or polished—it’s wet, blue, stitched, and swollen with spirit. The kind of funk you don’t scrub off. The kind that stays. His cyanotypes are not declarations; they are wetlands. They hold what seeps through.

Lojithan remind us that memory, like the sacred, often settles in the places we try to forget.

P.S. Here’s my swampy playlist for those brave enough to wade the funk…

Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum is on view through 23 June at Paradise Road Saskia Fernando Gallery, 41 Horton Place, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka.